This article is one of a series of 50. Together they explore the history and culture of India from her most ancient civilisations to the nation’s ambitious space programme. All 50 articles will be collected into a digital book and published in due course. To receive a FREE copy of the book, simply register for my newsletter here.

June 20, 1756. A night that continues to live in infamy in the annals of the British colonial era in India. On that sweltering summer night, one hundred and forty-six British prisoners – including two women, several wounded men, and a number of Indian civilians – were herded into a tiny dungeon inside Fort William in Calcutta. The eighteen feet by fifteen feet lock up had only two small windows, almost no natural light, and was known as the fort’s ‘black hole’. The climate at that time of year was roasting and it wasn’t long before the prisoners were trampling on each other in an attempt to snatch a gasp of air from the tiny windows.

Throughout that night, they begged for mercy, for water, for a show of decency from their captors. Their pleas and prayers went in vain.

The next morning, when the door was unlocked, the dead came tumbling out. A quick count revealed that only twenty-three of the prisoners remained alive.

At least that’s how the story goes.

The truth of the Black Hole of Calcutta may be not be quite so cut-and-dried.

First, a little scene-setting.

By the end of the seventeenth century, power in the Mughal empire that ruled over much of the subcontinent had fallen into the hands of the nawabs, provincial governors – with the trappings of sovereigns – presiding over regional territories. Meanwhile, the British, relative newcomers to the subcontinent and represented by the East India Company, had established a trading base in Calcutta in the 1690s, building Fort William as a defensive measure. They quickly became influential across the region, but this nascent power base came under threat in the mid 1700s from competing French interests.

In response, the British garrison, suspecting imminent hostilities, began to strengthen Fort William’s defences. Here the law of unintended consequences may have taken effect.

The Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-daula, newly succeeding his grandfather in 1756, and fearing the increasingly aggressive British posturing, sent orders to the British Governor of Calcutta to stop work on the fortifications.

When the British took no notice, the impetuous Siraj-ud-daula marched on Calcutta with an enormous army – a force of some fifty thousand men, fifty cannon, and, for good measure, a few hundred elephants.

The nawab’s forces arrived on June 16th, 1756, and began to move through Calcutta, encountering little opposition. The city’s British residents ran for cover to the ships in the harbour. Behind them, remained a garrison of just one hundred and seventy English soldiers, tasked to defend the fort. The garrison was commanded by John Zephaniah Holwell, a tax collector with no military experience – he surrendered on June 20th.

That night, according to his own account, one hundred and forty-six prisoners were marched into the ‘black hole’.

His description of the event – summarised above – was written after his return to England the following year, in the dramatically entitled A Genuine Narrative Of The Deplorable Deaths Of The English Gentlemen And Others, Who Were Suffocated In The Black Hole. The story caused an instant furore, stoking rage against Indians and a rabid nationalistic fervour throughout Britain.

A relief expedition led by Robert Clive, an East India Company lieutenant, was immediately assembled and arrived in Calcutta in October 1756.

Within a few short months, after a prolonged siege, Fort William fell to the British.

Less than a year later, in June 1757, Clive and a force of just three thousand, defeated the nawab’s army at the infamous Battle of Plassey, where the informal British policy of ‘divide and rule’ was employed to stark effect.

Deposing Siraj-ud-daula, Clive replaced him with his uncle Mir Jafar, a key commander in Siraj-ud-daula’s forces, to whom he had promised the ‘throne’ in return for Jafar sabotaging Siraj-ud-daula’s efforts during the battle. For this privilege, Jafar paid Clive the astronomical sum of £235,000. More importantly, he gave the East India Company power to tax Mughal lands and command Mughal troops.

Overnight the East India Company went from being merely powerful traders to India’s de facto rulers, a turn of events that most Britons looked upon with great favour – finally, they had an excuse to ‘civilise’ the subcontinent. The fact that India had had many advanced civilisations for thousands of years was completely lost on the invaders.

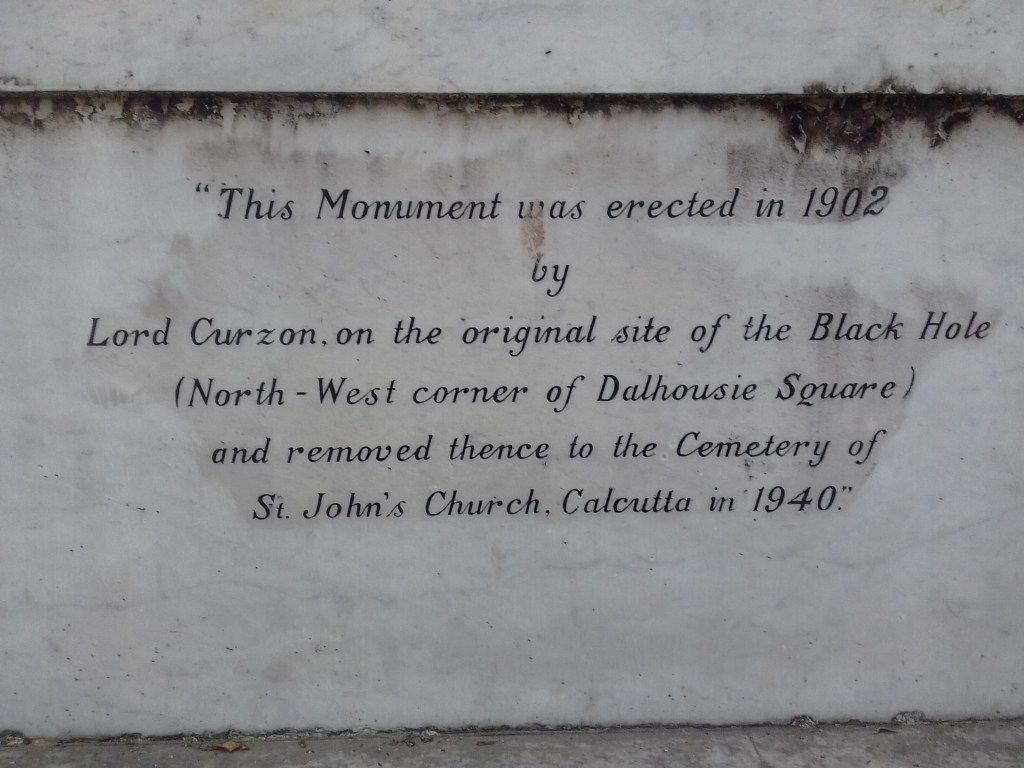

The success of the British at Plassey is often cited as the start of the colonial era in India, an era that would last uninterrupted until independence in 1947. Over time, the Black Hole incident attained mythical status among the colonisers as a demonstration of British stoicism, and was used as propaganda to smear Indians as capable of the worst sort of barbarism.

And yet… Many have long disputed Holwell’s defining account.

In 1915, scholar J.H. Little published an article entitled The Black Hole–The Question of Holwell’s Veracity in which he pointed out several flaws in the Englishman’s story. He showed Holwell to be an unreliable witness and claimed the incident was exaggerated by Holwell in an attempt to pass himself off as a hero.

Indian scholar Brijen Gupta, writing in the 1950s,suggests that the total number of prisoners shut in the ‘black hole’ was probably sixty-four, of whom twenty-one came out alive. He has also produced evidence that he claims refutes the notion that Siraj-ud-daula ordered the prisoners to be shut in. He suggests that the nawab knew nothing about the imprisonment, and subsequent deaths, until afterwards.

Where lies the truth? The best that can be established is that the captives marched into the dungeon that fateful night numbered between sixty-four and sixty-nine and no more than forty-three of the garrison at Fort William was unaccounted for afterwards. Therefore, it is most likely that forty-three people died that night, in terrible circumstances.

Whatever the numbers, the incident remains one of the most notorious of many brutalities – on both sides – to have marked the British time in India.

This article is one of a series of 50 that I will be publishing on my website. Together these pieces explore the history and culture of India from her most ancient civilisations to the nation’s ambitious space programme. You can read all 50 pieces here.

All 50 articles will be collected into a digital book and published in due course. To receive a FREE copy of the book, simply register for my newsletter here. The newsletter goes out every three months and contains updates on book releases, articles, competitions, giveaways, and lots of other interesting stuff.

My latest novel, Midnight at Malabar House, is set in India, in the 1950s, and introduces us to India’s first female police detective, Persis Wadia, as she investigates the murder of a top British diplomat in Bombay. Available from bookshops big and small and online, including here.

Thanks for sharing ” The Black hole of Calcutta”, the incident about which I never heard of and I am sure most of the Indians don’t know.

Thankyou

LikeLike

Thank you! To be honest I don’t think a lot of English people understand what really happened either!

LikeLike