This article is one of a series of 50. Together they explore the history and culture of India from her most ancient civilisations to the nation’s ambitious space programme. All 50 articles will be collected into a digital book and published in due course. To receive a FREE copy of the book, simply register for my newsletter here.

One of the great ironies of history is that Mohandas Gandhi, a man who changed the world through non-violence, died in an act of supreme aggression. Gandhi – called the Mahatma by his devotees, meaning ‘great soul’ – spearheaded the campaign for Indian Independence in the first half of the twentieth century. That campaign culminated in India becoming a sovereign nation on August 15, 1947, but also led to the country being divided into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan – the historical cataclysm known as Partition.

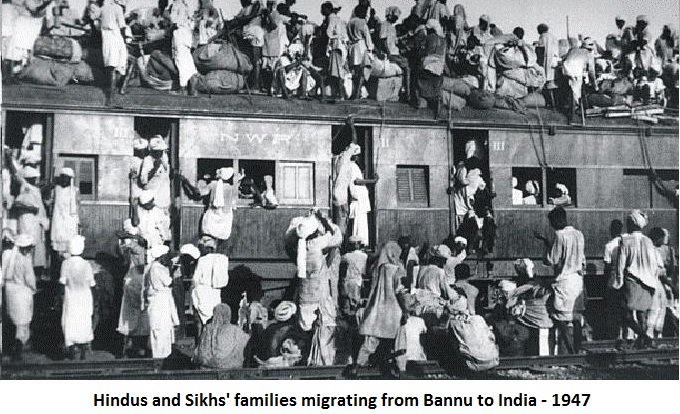

Gandhi’s dedication to satyagraha – literally: ‘insistence on the truth’ – earned him the support and affection of hundreds of millions of Indians. Alas, his own example could not prevent the communal disharmony that broke out across the country before, and after, Partition became a reality. Widespread rioting saw thousands dead and millions displaced.

Gandhi, horrified by the violence between Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, and the eviction of thousands from their homes, attempted to restore harmony using the methods that had worked for him in his long fight against the British.

On 13 January 1948, he undertook a fast unto the death, a tactic he had successfully employed during the Quit India years. His objective was to shame those who continued to participate in communal strife into adopting a more conciliatory outlook.

Messages of support flooded in from around the world. Some Hindus, however, believed that Gandhi should never have agreed to India being partitioned in the first place and that his insistence on non-violence and non-retaliation prevented them from defending themselves against the nation they saw as the ‘new enemy’ – Pakistan.

Some even advocated that he should be allowed to die.

On 20 January, a group of Hindu nationalists made an attempt on his life in Delhi, where Gandhi was living at Birla House, detonating a bomb just yards from him. Gandhi was unharmed and undeterred. ‘If I am to die by the bullet of a madman,’ he said, ‘I must do so smiling. There must be no anger within me. God must be in my heart and on my lips.’

On 29 January one of those nationalists, Nathuram Godse, a thirty-seven-year-old Hindu activist, the son of a postal employee, returned to Delhi.

At 5:17pm on the afternoon of the 30th, the 78-year-old Gandhi, frail from fasting, was being helped across the gardens of Birla House by his great-nieces on his way to a prayer meeting when Godse emerged from the crowd, bowed to him, and shot him three times at point-blank range in the stomach and chest with a Beretta automatic pistol.

Witnesses later stated that Gandhi raised his hands in the Hindu gesture of greeting, as if welcoming his murderer, before falling to the ground. Some said that he cried out, ‘Hey, Ram’ (‘Oh, God’). He died within half an hour.

Godse, meanwhile, tried but failed to shoot himself and was seized and taken away before the crowd could lynch him.

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, his voice breaking, addressed his countrymen with emotional words over All-India Radio: ‘Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives, and there is darkness everywhere, and I do not quite know what to tell you or how to say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the father of the nation, is no more.’

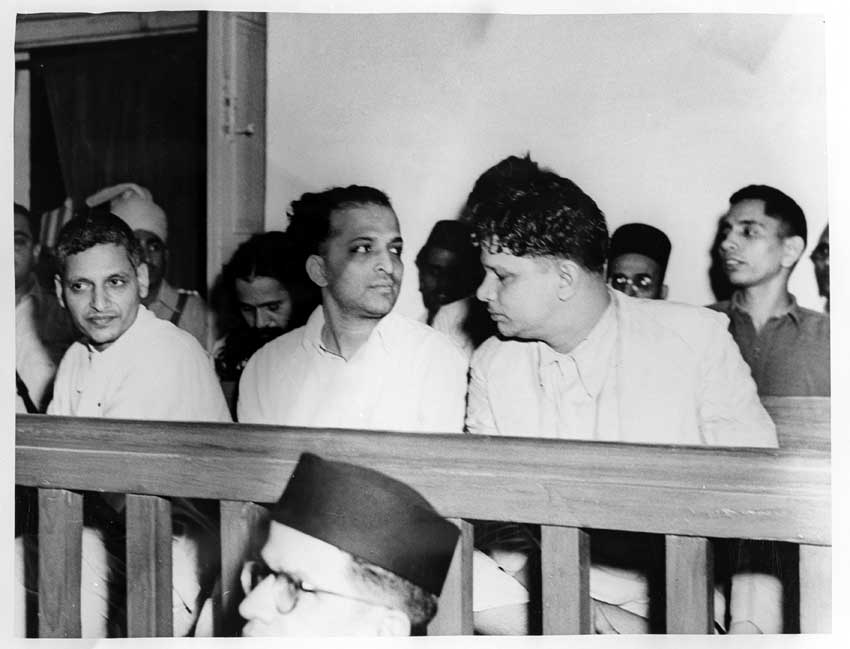

Within the year, Godse and several conspirators were tried in court at Delhi’s Red Fort.

At his trial, Godse, a devout Brahmin – a Hindu of the highest caste – did not deny the charges nor express any remorse, stating that he killed Gandhi because of his complacence, holding him responsible for the violence of Partition.

Godse was found guilty and executed in 1949.

The impact of Gandhi’s killing cannot be understated. Gandhi’s assassination dramatically altered the Indian political landscape. His death helped marshal support for Nehru’s new government and legitimised the Congress Party’s control over the country, a political dominance the centrist party enjoyed for decades until the advent of a strong right-wing opposition.

My latest novel, The Dying Day, is set in India, in the 1950s, and features India’s first female police detective, Persis Wadia, as she investigates the disappearance of one of the world’s great treasures, a 600-year-old copy of Dante’s The Divine Comedy stored at Bombay’s Asiatic Society. Soon bodies begin to pile up… Available from bookshops big and small and online. To see buying options please click here.

This article is one of a series of 50 that I will be publishing on my website. Together these pieces explore the history and culture of India from her most ancient civilisations to the nation’s ambitious space programme. You can read all 50 pieces here.

All 50 articles will be collected into a digital book and published in due course. To receive a FREE copy of the book, simply register for my newsletter here. The newsletter goes out every three months and contains updates on book releases, articles, competitions, giveaways, and lots of other interesting stuff.